In the 1930s, as Europe cowered under the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich, another power shift reset the automotive world order.

Infused with a bottomless bankroll, the marching orders of nationalism, and Europe’s best Grand Prix drivers, German automakers such as Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union (which would eventually become Audi) overtook French and Italian automakers that had once reigned the sport.

The landmark Silver Arrow race cars featured tubular frames, sleek bodies, and massive supercharged engines. They broke virtually every speed record of the time, and Germany seemed like an indomitable foe, both on the race circuit and in politics.

But the German Goliath would not go without a challenger, and that challenger was an underdog Jewish driver bankrolled by a pioneering American woman.

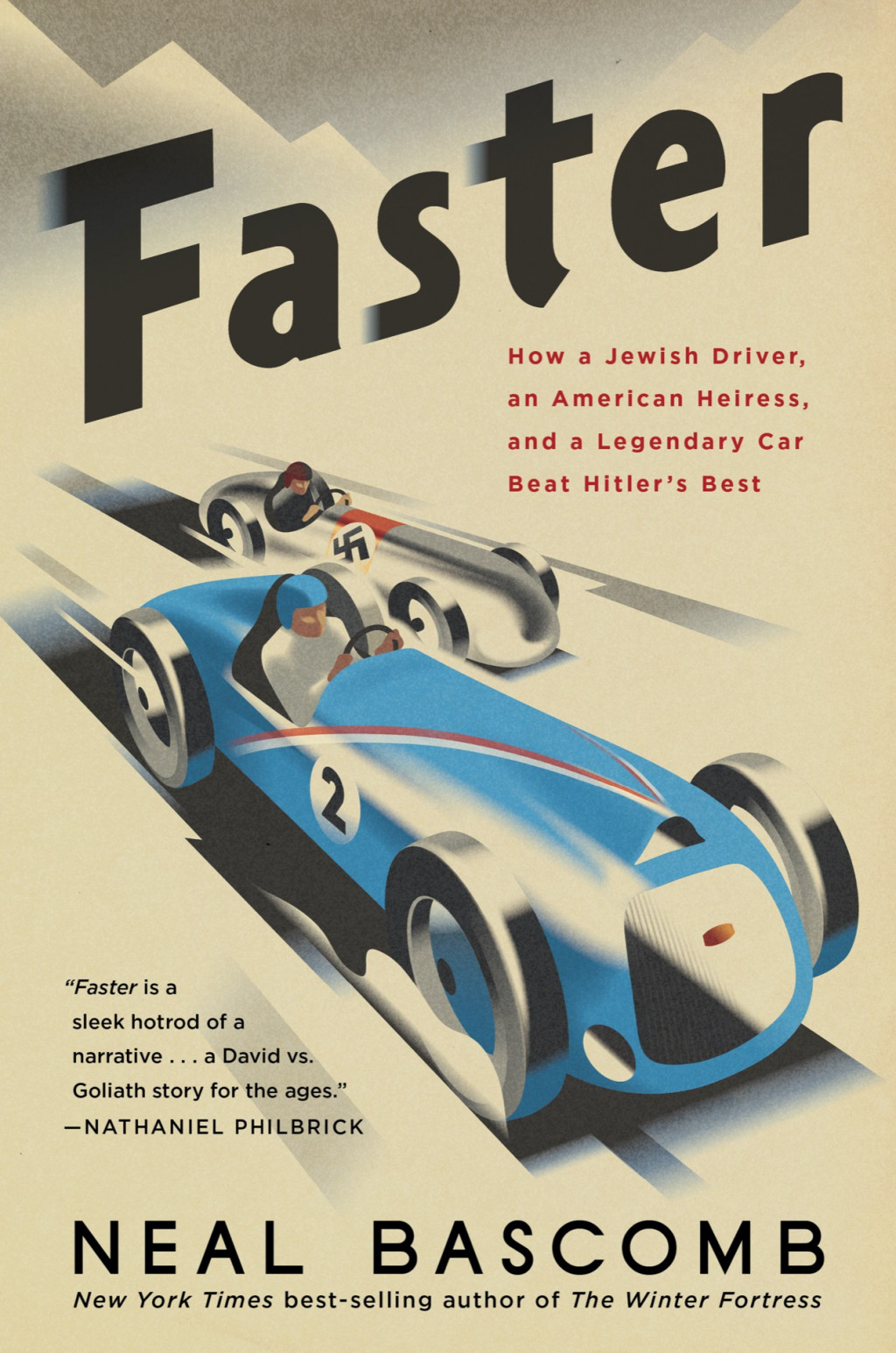

That is the world of “Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best,” by Neal Bascomb.

“Death, rivalry, betrayal, and politics—together they had irrevocably riven apart the Grand Prix world,” Bascomb writes in what he calls his first “car book.”

The 48-year old married father of two is The New York Times bestselling author of “The Winter Fortress” and eight other books, several of which take place in the WWII era. Despite that backdrop, “Faster” is about the pursuit of excellence on the track and under the hood.

“I’m not a ‘car guy’ but I like driving,” Bascomb, who drives a Subaru Outback, said in a phone interview from his home in Philadelphia. “I find the open roads almost meditative. You get in a zone, at ease, it’s a nice escape in some ways.”

But “Faster” isn’t about the personal joy of driving. The sweeping story unfolds like a race, with the narratives of three central figures brought together in pursuit of one goal, and how that goal escalates and deepens page after page until the last heart-pounding lap. The stakes are high—not only to be the best driver with the best time, but to compete in the boom times of automotive engineering that far outstripped any safety considerations and to stave off the lethal march of fascism and Hitler’s Germany.

MA: You’ve unearthed an original story taking place in the shadows of the global upheaval of WWII. How?

NB: I typically find stories you might have heard an inkling of or you’ve read a paragraph of it in another book but it’s not blown up into a whole book. I saw this snippet of Peter Mullin (owner of Mullin Automotive Museum in Oxnard, California) showing his Delahaye 145 at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, and this snippet was about how Hitler pursued this car when he invaded France, and they hid it from him. That was it. I looked a little further and reached out to Evelyn Dreyfus, René’s niece, and she sent me a bunch of materials and I was kind of hooked there.

MA: So your interest in the story did not come from racing at all or even from automotive…

NB: No, it came from the people. I was fascinated by René Dreyfus, by this Jewish driver who didn’t consider himself Jewish yet became a symbol of a Jew beating the Germans. Then Lucy Schell, who is this absolute tiger of a person, an original, a pioneer, the first woman to run her own Grand Prix team and build her own car, yet you’ve never heard about her.

And then Rudi Caracciola was also fascinating to me. He was by no means an ardent Nazi, but he compromised himself so he could drive, and he was willing to be that “Champion of the Third Reich” just so he could get behind the wheel of the fastest car in the world.

Lucy Schell

MA: How would you describe this era’s place in not only the history of motorsport but generally?

NB: I haven’t spent my life in the history of the automotive world, but I would venture to say it is one if not the biggest leaps forward in the technology of these cars. In the late 1920s, race cars were going 100 mph pretty efficiently; a few years later these cars are going upwards of 250 mph with very little advancements in terms of safety. The suspensions systems, engine power, braking—the Germans had made these massive leaps forward in speed and abilities. And it does have this really dark undertone: Mercedes, Auto Union, and how much of them were saved, supported, and advanced by Hitler and the Third Reich, and how much of a role those executives played in supporting that regime.

MA: There’s the broader metaphor that the German automotive industry is ascending while the French automotive industry is plummeting.

NB: Absolutely. The number of French automobile companies went from hundreds down to a few dozen in just a few years, with Bugatti being in the top in the 1920s, then being near the bottom in the ’30s. You could say the same thing about Delahaye, until Lucy came along.

MA: The book shows how instrumental Germany’s auto industry—and by extension its hugely successful racing program—was in carrying out Hitler’s vision. Yet there were only these small forces opposing it.

NB: There were very few instances where I had statements from one of the principals overtly saying we’re here, we’re going to be divine avengers and beat the Germans. Their actions said that but the overt statements were few and far between. In some ways it’s a benefit and others a hindrance. I couldn’t say Lucy leaned over the edge of the car at Pau and said, “Let’s beat the Germans.” We didn’t have that material.

Bernd Rosemeyer at the start of the speed record attempt that cost his life, January 1938

MA: There were dozens of key characters and at least 50 races chronicled over as many locations in “Faster.” How did you narrow it down to a very specific place in time—1930s Grand Prix racing—populated by certain key people when there were so many other things going on at that time?

NB:I feel like one of the hardest parts of writing this was choosing what blend of races to feature, because if I were to feature 10 Monaco races it would blur together. So I tried to write one particular race in one particular time—I had this huge excel spreadsheet of every race from 1930-1939 and then tried to thread races with backstory and history of the characters all while trying to keep the book moving forward. I wrote a book about running and racing called “The Perfect Mile” where I had to pick moments to feature. Same here. And for some people 50 races might be too many, and 50 might be too few.

MA: There are passages, specifically on the course outside the Montlhery autodrome for the Million Franc prize and in the 1938 Pau Grand Prix, but other moments, where you not only put the reader there, but also let us participate as a spectator, from above, and from beyond the embankments.

NB: There’s probably only five or six races that are really profiled like you’re there. La Turbie hill climb, René’s first Monaco race, Caracciola’s first Grand Prix win, the Million Franc prize, Pau. Oh, and the speed record trials, and Lucy Schell’s Monte Carlo rally, those are the ones that stick out to me.

1938 Pau Grand Prix, with Rudi Caracciola, front, Silver Arrow, and Rene Dreyfus, next, Delahaye 145

MA: It’s safe to presume you have done some driving?

NB: I’ve driven some of these old cars, I was a passenger in the Delahaye 145, but I haven’t done any competitive driving. The vantage point of putting readers there is spending the past two to three years being submerged in 1930s Grand Prix racing and reading thousands of pages of race accounts and driver memoirs, interviews and literature, and just being in that world. In Pau, the automobile club there, they had these 3x3-foot large scrapbooks that were probably 150-250 pages of that one race, the 1938 Pau Grand Prix. Every newspaper article from the week before to the week after, hundreds of hundreds of articles that allowed me to get into the minutia; the power is in the minutia. I had a lot of material.

MA: This is a David and Goliath underdog story on so many levels, ethnicity, age, gender, nationalism, and then in the Pau Grand Prix there is this super-handling Delahaye (the 145 had a 248-horsepower 4.5-liter V-12 engine with three camshafts) as David and the Mercedes W154 (a low-slung 427-hp 3.0-liter supercharged V-12) as Goliath.

NB: Yeah, an engine on wheels, right?

MA: It reminds me of racing a Miata versus racing a Hellcat. Is there a modern comparison that you would make, beyond David and Goliath?

NB: You could find a lot of my books are David and Goliath stories probably because when I was nine years old I watched the Americans beating the Russians in the 1980 Olympics in hockey, and I’m probably just repeating that over and over again in my stories.

MA: Those racing passages made me want to get out and drive, which might be the only acceptable leisure activity right now. What was your intent for this project and what do you hope it achieves?

NB: For the car buffs out there I hope this is a narrative like A.J. Baime’s “Go Like Hell: Ford Ferrari, and Their Battle for Speed and Glory at Le Mans.” It draws you in like a novel. AJ’s book was an example for me.

For general readers, for all readers, I hope these individuals like René and Lucy come alive. I think they are inspiring people, their stories are inspiring, and they are proof that everyone has a role to play in the world to make it better, to do something remarkable. If readers take away that, I’m super pleased.