Back in 1974, I was freelancing out of my Los Angeles photography studio and was contacted by Wanda Coleman, Los Angeles poet and editor in chief of Player’s Magazine to do a photo session with street racer “Big Willie” Robinson. The photos would illustrate a story that a colleague of mine, Steve Alexander was writing.

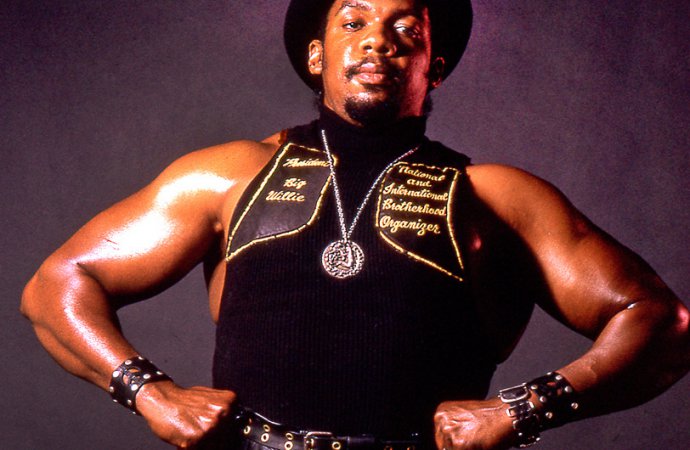

I had heard about Andrew Robinson III, an imposingly muscular 6-foot, 6-inch figure and Vietnam veteran who commanded respect of the youth of South Central Los Angeles during the 1970s. He was on a mission to end gang violence and racial unrest through drag racing.

In the wake of the 1968 Watts riots, Big Willie Robinson developed a way to use drag racing to change the growing tension of street violence among young people in the area. Robinson’s car was a car as large and intimidating as he was, a 1969 Orange Hemi Daytona Charger that had appeared in the movie "Two Lane Black Top."

Drag strip flyer

”When you get around cars, man, there ain’t no colors, just engines,” he told the Los Angeles Times in a 1981 interview.

In his bowler hat, Robinson was the king of the street-racing scene in the late 1960s and into the 1970s in East LA, where gangs and drugs were on the rise. With his wife, Tomiko, he organized the International Brotherhood of Street Racers in 1966 as a way of redirect South Central youth from crime and violence.

“Peace through racing,” he said.

‘Big Willie’ stands on a pickup truck as he explains the rules of racing to participants

Working with officials and local police, Big Willie and Tomiko were the driving force behind the building of Brotherhood Raceway Park on Terminal Island in LA Harbor’s Terminal Island. Willie knew, the then-mayor of LA, Tom Bradley. The mayor endorsed Big Willie’s efforts and helped him in many ways, including in the plans for the Terminal Island Race Track in 1974.

“I think it’s a great idea,” Bradley told Eye Witness News LA in 1977. “It provides not only an opportunity to give these youngsters an outlet, but it helps build brotherhood.”

Big Willie and Tomiko were together for nearly four decades. “My life partner, my security, my everything,” he said of her “We worked together for 38 years and raced together and she died in my arms (in 2010). It ain’t easy,” Big Willie said before his passing in 2012 at the age of 69.

A Chevy Nomad does a wheel stand at Terminal Island drag strip | Brotherhood Raceway Park photo

“Big Willie could go up to gang members from two different gangs who were ready to kill each other and have them put down their weapons,” recalled Paul Norwood, an executive vice president of the National and International Brotherhood of Street Races.

Tomiko Robinson

I got to know Big Willie and Tomiko through the Brotherhood of Street Racers and found that his main goal in life was to help young people stay off the streets and make a better life for themselves. By getting them drag racing on Terminal Island, he accomplished this and saved thousands of young people from landing in jail, or being killed.

Larger Than Life podcast, image by LA Times

In a continuing effort to preserve Big Willie’s mission, the Los Angeles Times is running a podcast, Larger Than Life, and plans a major printed story about him in the coming weeks. The podcast includes a trailer video.

This article, written by Howard Koby, was originally published on ClassicCars.com, an editorial partner of Motor Authority.