Michael Santoro’s eyes twitched, then dropped, as he almost fell asleep at the wheel. He had been up nearly 36 hours straight, and had pulled long hours ever since he took over as designer for the reborn supercar that would carry the star-crossed Vector name.

“It was insanity,” he recalled. “I almost crashed.”

He still had weeks of work to go on the project—and now, the company’s Indonesian owners wanted a new logo for the new Vector. They wanted him to invert the car’s existing V-shaped logo to look like a volcano, which is an important symbol in Indonesian culture and history.

With critical pieces of the car’s interior left unfinished, the request seemed crazy. Crazy was par for the course at Vector Aeromotive, which was in the midst of trying to revive one of the craziest supercar brands, and stories, of the prior decade.

In late 1995, Santoro, the man behind the first Jeep Easter egg, as well as the Chrysler Cirrus and Dodge Stratus sedans, found himself responsible for finishing the design details of the Vector M12 supercar—as well as three additional Vectors including an M12 targa, a front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible, and an El Camino-like mid-engine 2+2.

Unlikely to ever exist, these models never saw the light of day. They were unknown outside of a select few at Vector, until now.

1993 Vector WX-3 prototype

Vector’s crazy, all-American saga

Say the name Vector to 1980s car enthusiasts, and it conjures memories of the wedgy supercar that shattered speed records and bank accounts, not to mention production timelines. What began as Vehicle Design Force in the early 1970s morphed into Vector, which produced its W8 supercar in 1990 after nearly two decades of fundraising.

Gerald Weigert led the quixotic company to fame, then to ruin. A former design consultant for Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors, Weigert tried to follow in the footsteps of greatness and fell far short. Larry Griffin wrote in Car and Driver that Weigert was like “a back-yard Enzo Ferrari without the white hair, the dead son, and Fiorano test track, and the massive backing from Fiat.”

From day one Vector was plagued with problems: delivery problems, production problems, PR problems. Andre Agassi took delivery of one and took the company to task when his car overheated; Vector took the car back and refunded the tennis legend’s money. Worse, car magazines tested the W8 and found it wanting. Car and Driver clocked one in a 3.8-second 0-60 mph sprint, which was good enough to beat a Ferrari F40. But first one Vector’s transmission grounded to a halt while another’s engine continuously overheated.

One of the biggest W8 selling points was its top speed, which was variously reported as 218 or 242 mph. Csaba Csere, tech editor for Car and Driver back in the 1980s, told Hagerty in 2019, “the only way it could have gone 241 mph was if you’d dropped it out of a 747 at high altitude.”

Vector had financial problems, too. The W8’s base price rose to $450,000 by 1992 after building 23 cars. To enhance Vector’s finances, Weigert put together a deal to buy Lamborghini from Chrysler, end W8 production, and work on a new model named the Avtech WX3, which debuted at the 1993 Geneva motor show.

Vector ended up under the control of Indonesian company MegaTech, which also bought Lamborghini from Chrysler. Leading MegaTech was Tommy Suharto, the youngest son of the then-president of Indonesia. Leading the design charge for a new range of Indonesian-funded, American-designed supercars was Michael Santoro.

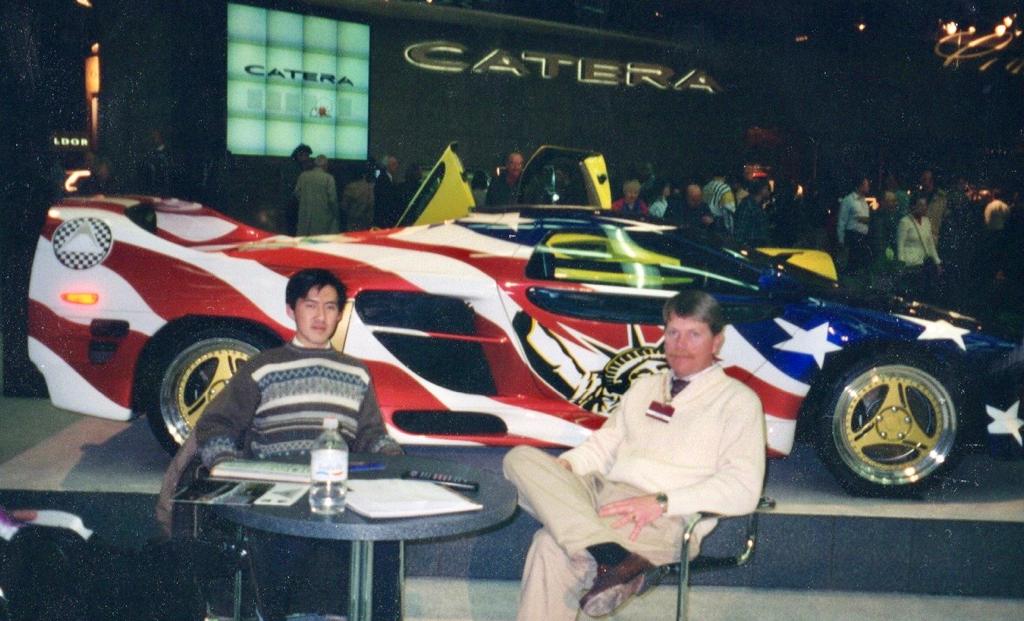

Vector M12 debut at the 1996 Detroit auto show with engineers Don Kamarga and Tom Foley, photo by Don Kamarga

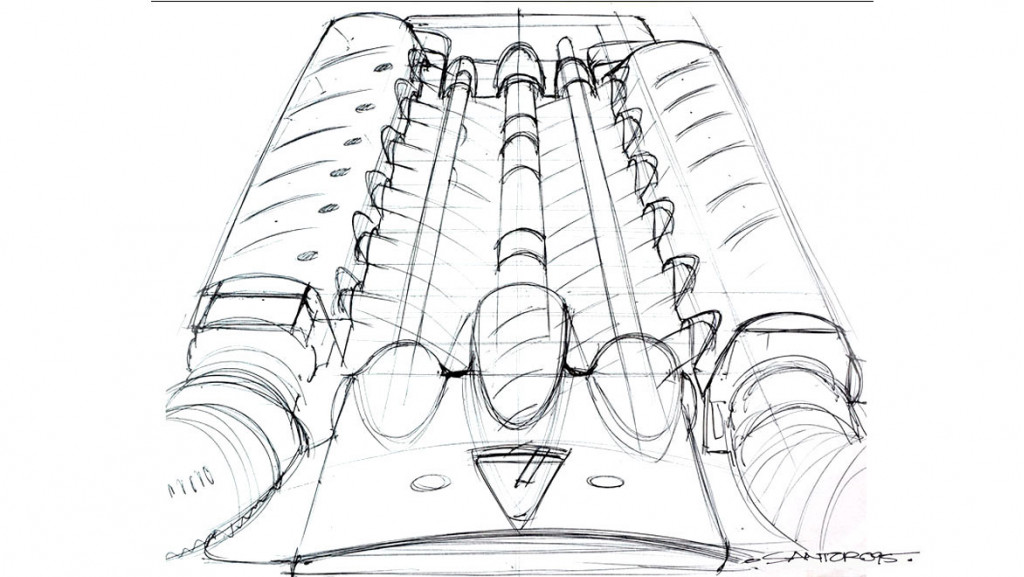

Vector M12 engine cover designed by Michael Santoro

Vector M12 brochure cover

Finishing the M12

Santoro had caught Vector’s eye in a 1995 New York Times feature story on his work on the Dodge Stratus and Chrysler Cirrus. In August, Santoro leapt at the opportunity to design supercars and to work with head engineer Ian Doble on what he thought would become the next great American supercar.

By the end of September, Santoro was commuting from his home in Brooklyn to Vector’s headquarters in Jacksonville, Florida, where Vector shared its headquarters with Lamborghini.

Santoro’s first task, laid out by then-Vector CEO D. Peter Rose and Doble––who had been the director at Lotus from 1951 until 1991––was to complete the design details of the M12 supercar ahead of its January reveal at the 1996 Detroit auto show. The work was intense and the hours long, and that’s when Santoro almost crashed when he fell asleep behind the wheel.

Vector M12 engine cover sketch by Michael Santoro

The M12 was a mishmash of parts, Santoro recalled. The front turn signals were from a Mazda Miata. The turn signal stalks, switches, and cabin lights were from the GM parts bin. When he arrived, the M12’s exterior was mostly ready, but it needed wheels and colors. Inside, details such as vent surrounds and gear selector had to be finished. It needed an engine cover.

Funding was far from secured, though Vector’s Indonesian investors believed that an American supercar positioned above the Corvette and Viper would work, even if it was built in a shed in the Florida swamps.

Production slowly began, and Vector eventually built about 16 cars. As it built the handfuls of M12s, it plotted three more cars to follow.

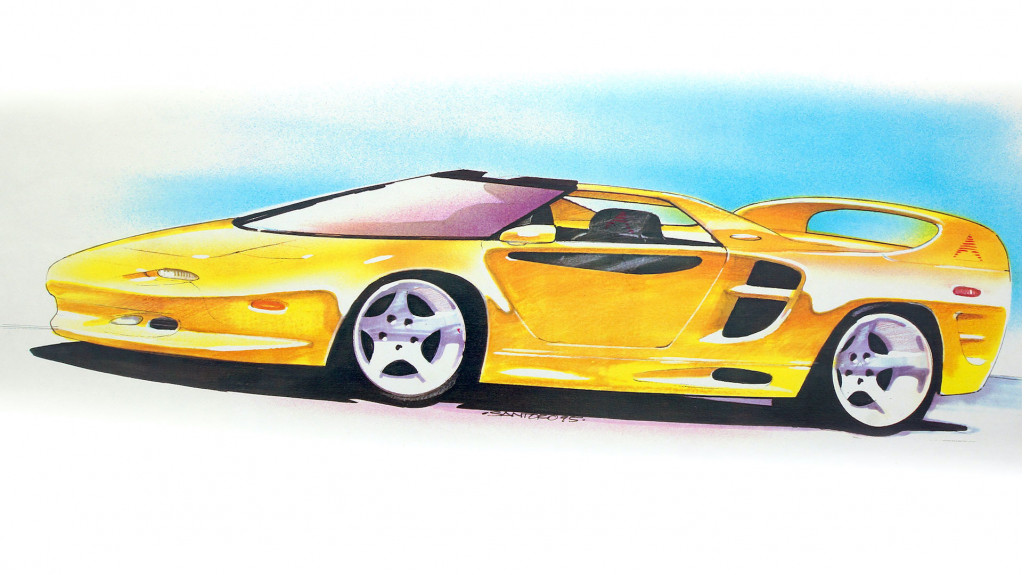

Vector M12 Targa design sketch by Michael Santoro

Targa talks

First, Doble tasked Santoro to design a targa version of the M12. The targa was slated for production 6-9 months after the M12 coupe, which would have put it in production near the end of 1996.

The targa model body style was an easy choice because “all they had to do was cut the roof off, test it, see how much it wobbled, and then just reinforce it,” Santoro said. Doble gave Santoro the task of rendering the topless M12 model with a simple directive: Let’s just see it with the roof off. No other design changes were planned. The project was viewed as a straightforward way to get another new model out the door.

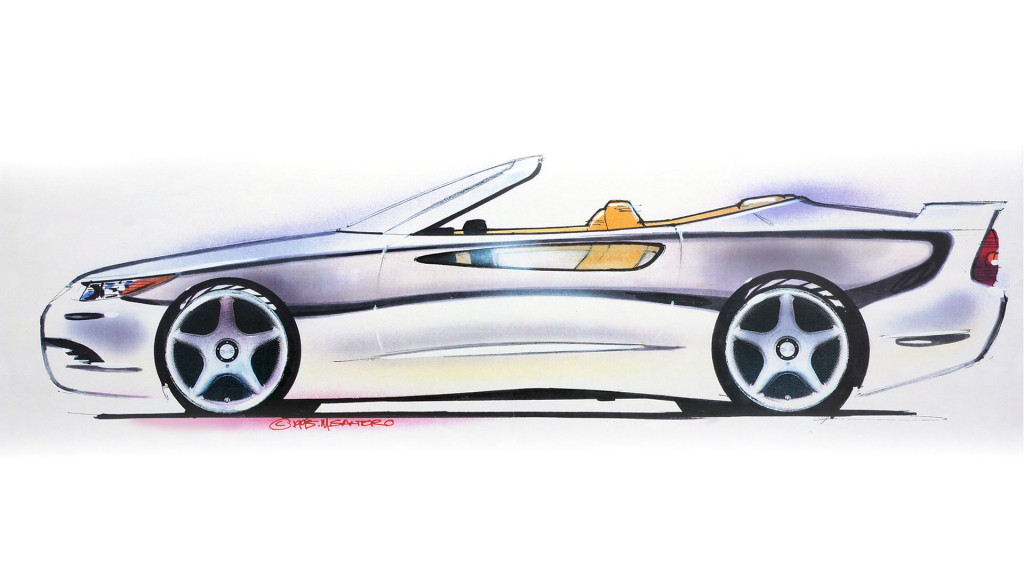

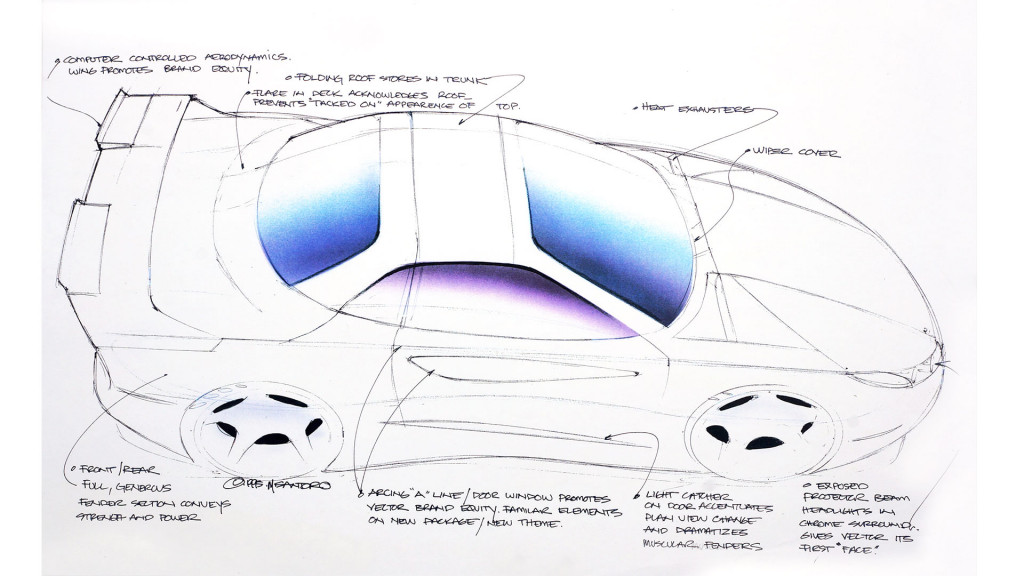

Vector front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible sketch by Michael Santoro

2+2 = 0

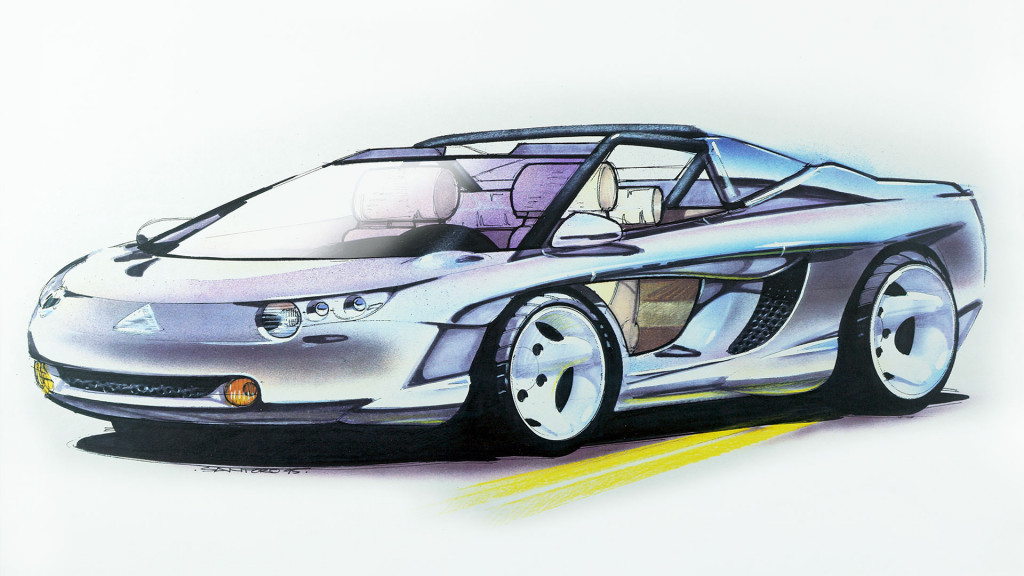

After the M12 coupe and targa, Vector planned to build a front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible. It was conceived as a more practical, everyday supercar at a lower price point. At the time, the M12 cost about $250,000.

The 2+2 was meant to be more of a grand tourer, “a bit more relaxed, it’s not so up on its toes all the time like the M12 was,” Santoro said. The plan called for this model to arrive either in 1997 or ’98.

The GT was meant to show where Vector would take the brand with an American aesthetic. Santoro drew the 2+2 with what he calls a lot of surface tension and a very three-dimensional design. It would have a Coke-bottle shape, like old American muscle cars. The peekaboo window on the door below the beltline carried over from the M12 as a trademark Vector design cue. The front end design, with its smooth nose, cat’s eye headlights, and three lower fascia intakes, was to become the face of Vector.

Vector front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector front-engine 2+2 hardtop convertible sketch by Michael Santoro

The car would also have active aerodynamics on the rear wing. Like Formula One with DRS––a system to control an adjustable rear wing to reduce drag––and the Bugatti Veyron received in the mid-2000s, flaps in the rear wing would flip up when the brakes were applied. This would increase the attack angle of the wing to create more downforce in corners. It would then neutralize on the street and the flaps would drop back down into the wing.

Santoro never ended up rendering the rear end or a detailed version of the interior. “I never got to do any development on them,” he said. “It’s like they’re frozen in time.”

The powertrain was never chosen either, but Vector wouldn’t use another Lamborghini engine like the Diablo’s V-12 in the M12. “It was going to be a big, powerful American engine,” Santoro said. Doble was no stranger to big American engines as he was in charge of the engine development of the 1990 Chevrolet Corvette ZR-1 during his time at Lotus.

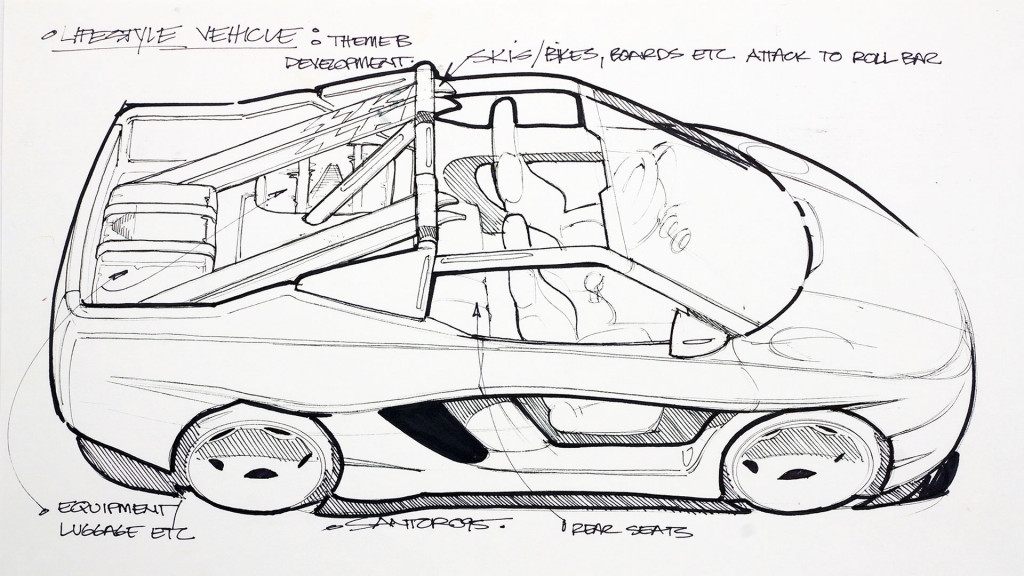

Vector open-top 2+2 lifestyle vehicle with an El Camino-like bed sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector open-top 2+2 lifestyle vehicle with an El Camino-like bed sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector open-top 2+2 lifestyle vehicle with an El Camino-like bed sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector’s own El Camino

Doble told Santoro that his third Vector design would be a small, lightweight, open-top 2+2 lifestyle vehicle with an El Camino-like bed, no windows, and skeletal doors.

The car/pickup was conceived as a fun-to-drive vehicle, one meant to be functional as like a Jeep Wrangler.

Doble was in charge of engineering for the Lotus Elan and Elise, but he was upset how much the Lotus Elise had been compromised to get it to production.

According to Santoro, Doble wanted something uncompromised, but functional—not just a track car.

Like the M12, Vector planned to build the lifestyle vehicle with a steel frame and welded chassis with body parts bolted in place. That meant it wouldn’t be any harder to build than the M12.

A short wheelbase would give the car go-kart-like handling. “This would be probably 25% closer to the Elise side than it would be to the M12,” Santoro said.

Vector open-top 2+2 lifestyle vehicle with an El Camino-like bed sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector open-top 2+2 lifestyle vehicle with an El Camino-like bed sketch by Michael Santoro

Vector open-top 2+2 lifestyle vehicle with an El Camino-like bed sketch by Michael Santoro

The overall design theme was animalistic with a raked stance, and tension between the front and rear surfaces, like a panther ready to pounce, according to Santoro. The exposed frame would mount accessories like off-road lights. Small sail panels aft of the roll bar draped down into the bed to cover part of the exposed roll cage and gave the car a finished look.

Once again, a powertrain was never chosen, but Doble and Rose discussed a boxer engine to keep the weight low in the chassis. At the time, Porsche, Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, and Subaru were making boxer engines.

Vector intended the 2+2 to be “a Swiss Army knife kind of a vehicle,” Santoro said. Different versions would be offered. Some would feature a raised ride height with off-road tires and others would get low-profile tires and a lower ride height for track use. None ever existed.

Vector M12 Flag Car, photo by Don Kamarga

Stumble and fall

The M12 was going to be the start of it all.

“I believe that they thought the M12 was going to be very successful,” Santoro explained. “I think that they believed that people were going to buy into the American supercar idea.”

Vector’s executives thought the M12 would bolster Vector’s stock price and generate the revenue needed to fund the lineup of future cars. It didn’t.

Santoro received a package drawing—what car designers get from the engineering team that has people, gear, and engine placement packaging laid out for the hard points—for the 2+2 lifestyle vehicle, but not the 2+2 front-engine hardtop convertible.

Purple 1996 Vector M12

The M12 passed all DOT requirements including crash tests, but the commercial success never happened. Vector didn’t have the precision to make the quality of car customers expected, Santoro said. Things broke and overheated. At one point, the side intake ducting into the radiator needed to be redesigned to keep the water temp level within check. The M12 underwent hot-weather testing in Florida, but it didn’t complete any extreme hot-weather or cold-weather testing, and it didn’t spend enough time sitting in traffic during development.

All the plans came to an end shortly after the M12 debuted at the 1996 Detroit auto show. Rose and Doble called Santoro in the spring of 1996 and said the entire thing was only going to last a couple more weeks as Vector was about to run out of money.

“The Indonesians pulled the plug,” Santoro said.

The reason? Rose told Santoro, Suharto “just got bored…something else interested him this week.”

Santoro said a total of 16 M12s were built. Two have either been crashed or lost to fires, leaving 14 in existence around the world.

Santoro looks back on the nine months between 1995 and 1996 like joining the circus. He worked on the bleeding edge of the auto industry, where crazy designs and crazy horsepower sometimes conjure enough magic to sustain a brand through a short burst of life. Vector had assembled a team of engineers with experience ranging from F1 to Corvette powertrains, but couldn’t pull it off without money.

The once and future Vectors were stillborn, and exist only in these drawings today, serving as another vaporware legend like the Dany Bahar-era Lotuses or some of today’s foundering battery-powered startups. Santoro left that future behind on a drawing board, not long before Vector left for good.

With Vector fully laid to rest, Santoro could finally get some sleep.